The troubling legacy of white democracy

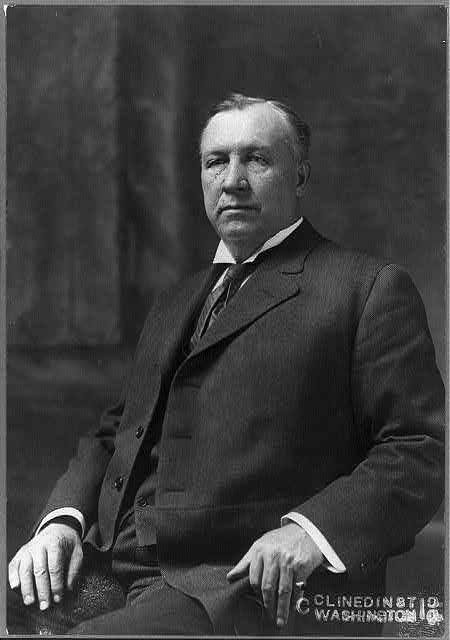

On December 9, 1905, in the little town of Baxley, GA, some 200 miles southeast of Atlanta, gubernatorial candidate Hoke Smith, who was the former U.S. Secretary of the Interior in the Cleveland Administration, outlined his plan for Black disfranchisement. Speaking to a group of supporters, Smith reflected on what he saw to be one of the key follies of federal intervention into the post-Civil War South. “The effort to make ignorant negroes rulers over their former masters,” Smith said, “brought upon our section suffering and losses exceeding the devastations of war.”

Like many southern politicians of the late 1800s to early 1900s, Smith was a white supremacist who believed the reconstruction period was a tale of horrors. The popular history consisted of stories of newly freed Blacks running rough shot through the South, dismantling everything that white southerners viewed to be good and right about southern society. As such, it’s not surprising that Smith focused his campaign for governor on whiteness. After making a case for removing Black Georgians from politics, Smith continued his Baxley speech by pointing out that Georgia was “white man’s country” and by making clear that “not only in the state at large, but in every county and in every community the white man must control by some means, or life would not be worth living.”

And so it was. After he won the governorship, Smith made sure that whites, and only whites, would rule Georgia. He shepherded an amendment to the state constitution that virtually eliminated the Black vote. “By the beginning of the new century,” according to historian Andrew W. Manis, “the arrival of Jim Crow and black disfranchisement had done much to reverse black progress and return African Americans as nearly as possible to their former, inferior place in the Southern pecking order.” Over the course of the next fifty years, white Georgians erected a white supremacist society that expanded Smith’s vision—making sure they claimed Georgia as “white man’s country.”

Georgia’s white supremacy, as well as the white supremacy of the rest of the Jim Crow South, depended on what Emory Univeristy professor of history Jason Morgan Ward has called white democracy. In his book Defending White Democracy: The Making of a Segregationist Movement and the Remaking of Racial Politics, 1936-1965, Ward described it this way:

When southern conservatives spoke of defending “white democracy,” they referred simultaneously to a racial worldview and a political order. They considered black disfranchisement and segregation essential to maintaining a society governed by and for whites. The survival of this racial order rested upon regional allegiance to the Democratic Party, which had long been the refuge for Jim Crow’s architects and guardians. As an outspoken white supremacist argued in the 1940s, “orthodox” southerners traced their political heritage back to Thomas Jefferson’s vision of “constitutional government and individual liberty.” But they rejected any attempt to update Jefferson’s qualified egalitarianism with “the newly evolved theory” that “men of all races have been found to be equally capable in every respect and… should be merged without distinction.” From its inception, the ideal of a “white democracy” rested upon allegiance to the “White Democracy” envisioned by the party founders.

As the new century matured and time raced toward the 1950s, many civil rights activists began questioning the legitimacy of this white democracy. Even so, southern segregationists found it difficult to let go of their understanding of democracy as white. For example, immediately after the Supreme Court ruled school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, a city official from Macon, GA said that the ruling was “a direct violation of states’ rights” and, as such, the Court’s “infringements have taken away the meaning of the word democracy.”

In the case of school segregation, the entrenched nature of white democracy throughout the American South guaranteed massive resistance to integration. Because white democracy placed the vast majority of political power in the hands of white political elites, the restructuring of society would require white acceptance. Commenting on combing the Black and white school systems in Macon, E. H. Houseworth, an African American math teacher at Ballard-Hudson Senior High School for Negroes, said, “everyone must accept it, especially the white people.” But several of those white people never did. And, as a result, the troubling legacy of white democracy still lingers in the politics of today.

More to come soon…

Primary Sources

Bennett, Howard. “Bibb School Men Expect to Work Out Problems.” Macon Telegraph, May 18, 1954.

“Hon. Hoke Smith on Taking the Ballot from the Negro.” Macon Telegraph, December 10, 1905.

Murphy, Reg. “Time Held Need for Segregation.” Macon Telegraph, May 18, 1954.

Secondary Sources

Manis, Andrew. Macon Black and White: An Unutterable Separation in the American Century. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2004.

Ward, Jason Morgan. Defending White Democracy: The Making of a Segregationist Movement and the Remaking of Racial Politics, 1936-1965. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.